Center for Parents & Children

The Center for Parents and Children opened in 1972 under the co-direction of Dr. Judith Kestenberg, a psychoanalyst who had been interested in the relationship between mother and child for many years, and Arnhilt Buelte, a movement specialist and retrainer. Kestenberg began a pilot project in 1953 in which she attempted to devise a method of movement notation that could record non-verbal expressions of mothers and infants. The motor rhythms in gratification, frustration, random movement and play were observed and recorded. In the later 50's and early 60's, with the help of the Sands Point Movement Study Group, a movement profile was developed which could assess infants, children and adults. In its current form, the profile can be correlated with Anna Freud's developmental profile.

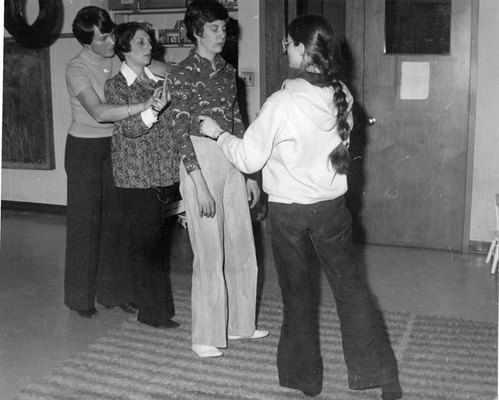

Arnhilt Buelte working with a parent

The Center was developed with the hopes of putting the findings of the Kestenberg Movement Profile (KMP) into practical use. Through the understanding of typical developmental movement and psychological functioning, retraining techniques were developed to help prevent emotional disorders and to avoid stress at vulnerable periods of development. One of the Center's aims was to optimize child-care by using movement as the tool for both assessment and retraining techniques. In addition music and art contribute to the assessment and retraining procedures.

The Center staff was multidisciplinary including 2 psychiatrists, a psychologist, a movement specialist, a creative art therapist and students. One or both parents participated at the Center with their children. There were usually 10-15 families involved in the program. Some came to the Center seeking guided support in raising their children, others liked the social contact and still others wanted to learn about child development and participate in research while they attended the Center with their children.

The Children's group included art, music, dance, fine and gross motor activities, free play, stories, and snack or lunch. The activities were designed to fit the developmental needs of the children. Part of the prevention philosophy was based on the concept of providing an optimal environment for growth in each developmental phase. Pleasurable creative art activities were offered which enhanced and supported the child's mastery of the developmental tasks. When special problems arose such as sleep disturbances, weaning, separation or anxiety, the staff worked with individual families. Movement, music or art interventions were instituted. The staff was informed of the familyÃs progress through weekly journals written by the mothers. If a significant event was happening in the family, such as a hospitalization, the birth of a new child, or a long business trip of the father, a special individualized book was written and illustrated to help the child understand and prepare for the event.

At the central core of the movement work was the concept of "attunement" or movement empathy, involving one form of harmony between movers. Regarding "complete attunement" in the mother-infant interaction, Kestenberg (1975) writes, "Complete Attunement is based on mutual empathy or on an excessive similarity between partners. There is not only a sameness of needs and responses, but also a synchronization in rhythms".

Attunement requires a process of kinesthetic identification. Muscular tensions felt in one person are also felt in the other. It is not necessary to duplicate the shape of the movement. During attunement, physical needs and feelings are being responded to. Visual attunement is accomplished by looking at, but not touching the mover. For example, if an infant was kicking his legs vigorously, in order to attune to him, one would not have to kick one's own legs. The process involves identifying how the child's kicking movement feels by simultaneously moving a body part (such as the hand).

"Touch attunement" is a similar process to "visual attunement" but includes the component of touch. An example is placing one's hand on someone and matching the tension changes felt in the hand by moving with the person in the same rhythm and degree of tension exerted by him. There may be little movement at all, just small changes in the contraction or stretch in the muscles. While attuning, the movement, either small or large, may be felt in the hand alone or it could spread throughout the whole body. Visual or touch attunement with a child or adult who is upset can lead to soothing. The degree of tension exhibited by the child or adult can be initially matched and then developed into less intense, more soothing patterns.

Attunement was used throughout the Center's program with individual children and during groups. In an art session with clay, for example, a child was squeezing or pressing the clay. To attune to the child, the pressing quality of his movement was felt by the attuner in some part of her own body. The movement did not need to be copied identically. As the group leader attuned with the child's pressing, she was communicating to him that she accepted his need to press which is in keeping with his movement phase of development and/or his movement preference for pressing motion. Other children in the group were invited to join in the clay pressing, and a feeling of community spirit developed around the action of pressing. In group movement sessions at the Center, the dance/movement therapist translated the children's initially scattered group movement into themes representing group movement needs. The dance/movement therapist combined her understanding of which movement phases in development the children were functioning with her skills in group leadership and, created expressive dances, dramas, improvisations and games.

Kestenberg Movement Profiles were constructed by trained notators of the children, and parents. These assessments revealed potential areas of vulnerability in the child and parent and areas of compatibility and incompatibility between family members. The profile was used to examine whether the child had reached an age-adequate developmental level. In both children and adults the KMP revealed areas of regression and chances for developmental progression.

Based on the information obtained from profiles, interventions were designed and implemented using movement, art, or music. Some of the goals of the interventions were to foster greater empathy between parent and child, to remove obstacles to developmental progression, and to strengthen the individual's resources so that he or she could cope with stress.

The Center staff was multidisciplinary including 2 psychiatrists, a psychologist, a movement specialist, a creative art therapist and students. One or both parents participated at the Center with their children. There were usually 10-15 families involved in the program. Some came to the Center seeking guided support in raising their children, others liked the social contact and still others wanted to learn about child development and participate in research while they attended the Center with their children.

The Children's group included art, music, dance, fine and gross motor activities, free play, stories, and snack or lunch. The activities were designed to fit the developmental needs of the children. Part of the prevention philosophy was based on the concept of providing an optimal environment for growth in each developmental phase. Pleasurable creative art activities were offered which enhanced and supported the child's mastery of the developmental tasks. When special problems arose such as sleep disturbances, weaning, separation or anxiety, the staff worked with individual families. Movement, music or art interventions were instituted. The staff was informed of the familyÃs progress through weekly journals written by the mothers. If a significant event was happening in the family, such as a hospitalization, the birth of a new child, or a long business trip of the father, a special individualized book was written and illustrated to help the child understand and prepare for the event.

At the central core of the movement work was the concept of "attunement" or movement empathy, involving one form of harmony between movers. Regarding "complete attunement" in the mother-infant interaction, Kestenberg (1975) writes, "Complete Attunement is based on mutual empathy or on an excessive similarity between partners. There is not only a sameness of needs and responses, but also a synchronization in rhythms".

Attunement requires a process of kinesthetic identification. Muscular tensions felt in one person are also felt in the other. It is not necessary to duplicate the shape of the movement. During attunement, physical needs and feelings are being responded to. Visual attunement is accomplished by looking at, but not touching the mover. For example, if an infant was kicking his legs vigorously, in order to attune to him, one would not have to kick one's own legs. The process involves identifying how the child's kicking movement feels by simultaneously moving a body part (such as the hand).

"Touch attunement" is a similar process to "visual attunement" but includes the component of touch. An example is placing one's hand on someone and matching the tension changes felt in the hand by moving with the person in the same rhythm and degree of tension exerted by him. There may be little movement at all, just small changes in the contraction or stretch in the muscles. While attuning, the movement, either small or large, may be felt in the hand alone or it could spread throughout the whole body. Visual or touch attunement with a child or adult who is upset can lead to soothing. The degree of tension exhibited by the child or adult can be initially matched and then developed into less intense, more soothing patterns.

Attunement was used throughout the Center's program with individual children and during groups. In an art session with clay, for example, a child was squeezing or pressing the clay. To attune to the child, the pressing quality of his movement was felt by the attuner in some part of her own body. The movement did not need to be copied identically. As the group leader attuned with the child's pressing, she was communicating to him that she accepted his need to press which is in keeping with his movement phase of development and/or his movement preference for pressing motion. Other children in the group were invited to join in the clay pressing, and a feeling of community spirit developed around the action of pressing. In group movement sessions at the Center, the dance/movement therapist translated the children's initially scattered group movement into themes representing group movement needs. The dance/movement therapist combined her understanding of which movement phases in development the children were functioning with her skills in group leadership and, created expressive dances, dramas, improvisations and games.

Kestenberg Movement Profiles were constructed by trained notators of the children, and parents. These assessments revealed potential areas of vulnerability in the child and parent and areas of compatibility and incompatibility between family members. The profile was used to examine whether the child had reached an age-adequate developmental level. In both children and adults the KMP revealed areas of regression and chances for developmental progression.

Based on the information obtained from profiles, interventions were designed and implemented using movement, art, or music. Some of the goals of the interventions were to foster greater empathy between parent and child, to remove obstacles to developmental progression, and to strengthen the individual's resources so that he or she could cope with stress.